Published in the Los Angeles Times

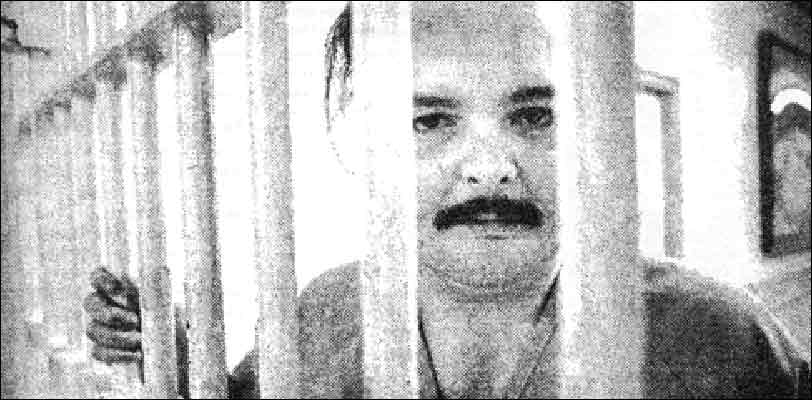

RALEIGH, N.C. — Eddie Hatcher dwells deep within the belly of the beast, held for trial in the cavernous yellow brick prison where North Carolina's most violent felons live out their days.

Hatcher is a large man with thick, black hair cascading to his shoulders. He strides into the visitors room at Central Prison, his silence masking the rage that turned this Tuscarora Indian into a caged animal.

Once he begins to speak, the words tumble out. The seething anger lies close to the surface. Hatcher has taken his share of licks tilting at windmills.

"I don't like it here," he says of prison life. "I despise it here."

It confines a man to sit day after day in a cramped concrete and steel cell. Prison life steals a man's soul and keeps him from doing battle against injustice.

As he sees it, Eddie Hatcher has been fighting those windmills a long time--and still has a ways to go.

"As bad it is, there has got to be some reason for me being here," Hatcher says. "I read and pray. I've got faith. Faith is what carried me through. I may get down once in a while, but it carries me through this."

Hatcher and another Indian, Timothy Jacobs, ran afoul of the law on Feb. 1, 1988, when they walked into The Robesonian newspaper in Lumberton, N.C., and took the staff hostage.

The vigilante action was intended to dramatize what the two men considered racially motivated injustice in Robeson County, where the population is nearly equally divided among whites, blacks and Indians.

Although the racial makeup of Robeson County is diverse, the power and the money are not. Whites control the purse strings and the local government.

Hatcher, on the day of the hostage-taking, was angry because an Indian friend was in jail and the newspaper had given better play to a story about a white judicial candidate than to a story about an Indian judicial candidate.

Armed with a sawed-off shotgun, he and Jacobs took 20 people hostage, released the black and Indian reporters and then 10 hours later released the whites unharmed.

The two men were tried on federal hostage-taking charges and found innocent by a predominantly black jury. The verdict surprised nearly everyone, including Hatcher, who clings to the hope he will also be acquitted of new state kidnaping charges he faces.

"If it were not for my political beliefs I would not be here," he says. "If I would have left the state (after the acquittal), they may not have brought these charges against me."

Hatcher reserves a fair amount of his wrath for Sheriff Hubert Stone, widely criticized by Indians who claim unfair treatment by the Robeson County Sheriff's Department.

Soon after Hatcher and Jacobs returned to Robeson County, Hatcher circulated petitions calling for Stone's impeachment.

"In three weeks we had 1,500 signatures," says Hatcher. "That was one of the main things I worked on from the time I was acquitted until I was indicted on state charges."

Hatcher and Jacobs fled after they were charged with 14 state kidnaping counts. Jacobs went to New York, where he hid out on an Onondaga reservation. Hatcher made his way to the Soviet Consulate in San Francisco, where he was arrested last May after being denied asylum.

Hatcher was extradited; Jacobs entered into a plea bargain with state officials and agreed to testify against Hatcher. He was sentenced to six years in prison, but likely will be released early.

Hatcher sees himself as a symbol of the repression of American Indians. From his cell, he writes to Soviet leaders accusing the United States of human rights violations and apparently believes his incarceration is such an abuse.

No trial date has been set for Hatcher, who last July 31 was taken from the Robeson County Jail in Lumberton to Central Prison in Raleigh, the toughest prison in the state.

A judge appointed a lawyer to represent Hatcher on the kidnaping charges, but Hatcher promptly fired the public defender, saying any lawyer representing him must embrace Indian issues.

"If a lawyer isn't willing to be arrested and go to jail for the cause, then I don't need him," Hatcher says.

Hatcher was moved at the request of Sheriff Stone after he and another inmate sued the sheriff, charging inhumane jail conditions.

A "safekeeper" law permits the transfer of pretrial prisoners to the Department of Correction for security or medical reasons.

"I feel it's a retaliatory effort on the part of the Robeson County Sheriff's Department and the North Carolina Department of Corrections," Hatcher says of his move.

"The county is paying them so much per day to keep me here and do their dirty work and deny me further constitutional rights," says Hatcher.

Hatcher's friends in Robeson County won't talk about him publicly. Privately they say they agree with the issues he raised, but not the method used.

"I never denied what I did," Hatcher intones in a thick, eastern North Carolina accent common to generations of Indians who learned English from Elizabethan settlers. "The whole world knew what I did. Anyone knew who kept up with the newspapers, magazine and the TV."

"I've seen one miracle. To be sure, you will see another," he says.

"There are people who call me fanatic," Hatcher concedes.

Eddie Hatcher died in prison in 2010 of AIDS, according to The Robesonian. He was 51. Hatcher was serving a life sentence for his role in a drive-by shooting in 1999. Hatcher served five years of an 18-year sentence for his role in the newspaper takeover. Terms of his parole prevented him from returning to Robeson County until the mid 1990s. Timothy Jacobs was paroled in 1990. He continues to be an activist on Indian issues.

Eddie Hatcher died in prison in 2010 of AIDS, according to The Robesonian. He was 51. Hatcher was serving a life sentence for his role in a drive-by shooting in 1999. Hatcher served five years of an 18-year sentence for his role in the newspaper takeover. Terms of his parole prevented him from returning to Robeson County until the mid 1990s. Timothy Jacobs was paroled in 1990. He continues to be an activist on Indian issues.